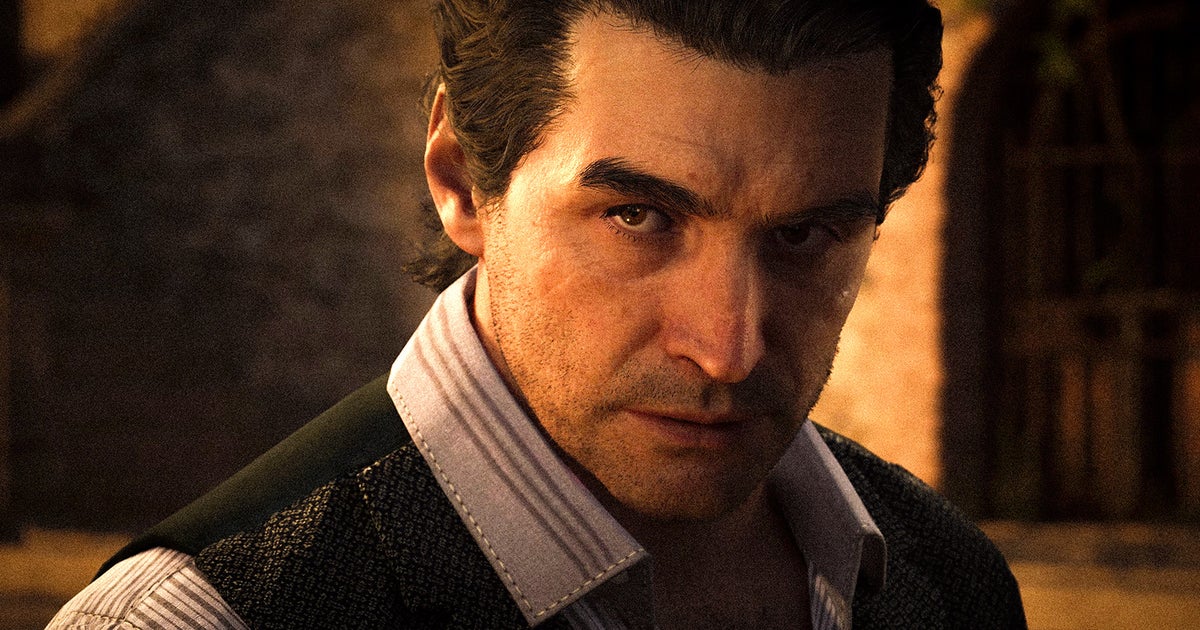

Short, smart, potentially a gamble: with Mafia: The Old Country, Take-Two grapples with the past and future of video games

Place and pacing are what Mafia: The Old Country does best. The artists and programmers at Hangar 13 have crafted an evocative and unflinching rendering of Sicily at the turn of the twentieth century: dappled lemon groves; vineyards snaking down steep hills; mines filled with indentured slaves, every face and fruit bowl lit with the exquisite, high-drama flair of a Caravaggio painting. The scriptwriters and narrative designers have kept up their end of the bargain, producing an ebbing, flowing mob story which puts as much emphasis on quietness as cracking skulls. Place and pacing are symbiotic: it’s through languorous car drives and trotting horse rides that we come to appreciate the setting. In almost every chapter, the volcanic Mount Etna smokes ominously in the distance, the skybox wielded as a perfect visual metaphor for the violence bubbling just below the surface of this picturesque island.

Mafia: The Old Country is both direct and deliberate which, in this era live-service, monstrous open-world bloat, feels precious. Many critics, including Eurogamer’s own inimitable Alex Donaldson, have stressed how the game feels like a throwback. The cover-based shooting and insta-fail stealth arrive like a PlayStation 3-era fever dream. So does the pseudo-open world (pseudo because you are following a tightly scripted path within an expansive game space absent of load screens). And yet, in spite of this anachronistic form, the experience feels as fresh as a sun-ripened Sicilian tomato. Indulge me in expanding the simile further. Mafia: The Old Country is juicy; its flavour is concentrated. And with a story that can be wrapped up in a compact 10 hours, completing the game is akin to consuming a delicious, single tomato. Compare it to, say, the 60-hour Assassin’s Creed Shadows, which demands that you gorge on an entire box.

How can it be that a third-person action-adventure crime game which tells a familiar rags-to-riches story can be considered fresh? That takes a little unpacking. Perhaps the fact that I’m making the argument at all is an indictment of where the triple-A space is currently at.

Watch on YouTube

Let’s start with the 2009 remarks of former Electronic Arts CEO John Riccitiello. Having released 50 games in 2009, Riccitiello said EA was planning on publishing 40 titles in 2010, and that the number could shrink further in years to come. “30 wouldn’t shock me at some point in the future,” said the CEO who had, incidentally, just laid off a massive 1,500 people, or some 17 percent of EA’s workforce (time is a flat circle, etc). By 2019, long after Riccitiello departed for what turned out to be a beleaguered stint at Unity, the number would be just ten.

In those comments, Riccitiello outlined a strategy shift adopted by many other publishers, including Take-Two, called “fewer, bigger, better” (shout out to Brendan Sinclair for covering this extensively during his time at GamesIndustry.biz). In short, throughout the 2000s and 2010s, the cost of development soared. Publishers were nervous about spending big on a wide slate of projects so they decided to focus on a smaller roster, opting to put more resources into making games prettier, more polished, and, yes, bigger. This became a kind of self-perpetuating ouroboros, a snake eating itself, becoming ever plumper with each development cycle until, well, the snake grew so fat that it began to choke. Joost van Dreunen, industry analyst and author of the SuperJoost Playlist newsletter, estimates an eightfold increase in average development budgets since 2000. He thinks Grand Theft Auto 6 (published by Take-Two, the publisher of Mafia: The Old Country) is set to break the $1bn budget barrier (excluding marketing and live-services costs), a four times increase from its 2013 predecessor.

“Fewer, bigger, better” has, in other words, become unsustainable, Sinclair tells me over email. “The cost of making and marketing those games grew so massive that there was functionally no way to get the necessary return on investment from anything but a lightning-in-a-bottle hit like Fortnite or Grand Theft Auto V,” he says. Crucially, “the cost of a flop at that scale was too much to tolerate.”

And so here is the Mafia: The Old Country: modest; bite-sized; tight, yet still clocking in at roughly four times the length of famously protracted mob epic, The Irishman. Sinclair ultimately sees the game as an “experiment” on the part of Take-Two to combat the “unsustainability” it helped foster – an effort to “find a way forward beyond the ‘fewer, bigger, better’ model.'”

Creatively, I’d argue the decision has paid off heartily. What a pleasure it is to play a game with triple-A production values which explores its themes with sharpened focus. Enzo is first and foremost a labourer: one day, he’s down the sulphur mine lugging rocks to pay off his debts; the next he’s carrying wine crates as bribes; the day after he’s hauling the corpses of those he’s killed. Large tracts of the game are essentially a walking sim, but one which heavily foregrounds the idea of role-playing. Walking as Enzo often feels more natural and rewarding than cavorting about in a sprint. You’ll want to take in all the postcard vistas, opulent interiors, and bulging market stalls. It’s also the best way to listen in on the conversations between other characters.

Contrast Mafia: The Old Country with the year’s premier blockbuster open-world offering Assassin’s Creed Shadows. I play the latter game marveling (in admittedly haughty fashion), at what I deem to be the novelistic detail of its sixteenth-century Japan setting: the knotty factional politics, aching poetry of the natural world, and deftly depicted socio-economic dynamics. The game whisks me away like a sweeping, thousand-page historical epic even if, dramatically, it ultimately feels like B-tier television. But novelistic is perhaps the wrong word to describe the depth and breadth of what Ubisoft has created. Perhaps the word I’m actually looking for is encyclopedic: the simulation it presents is all-encompassing and multi-faceted, just like Take-Two behemoths, Red Dead Redemption 2 and Grand Theft Auto V.

For all the craft and elegance of these supersized games, they’re undeniably shaped as much by C-suite business decisions as storytelling and design wit. Their sheer massiveness is the point, an attempt to hold our attention in a digital world constantly baying for it: short-form video on TikTok; the endless algorithm of Netflix; free-to-play gacha titles like Genshin Impact.

Sinclair doesn’t see the shorter playtime and smaller scope of Mafia: The Old Country as expressing some fundamental realisation on Take-Two’s part that games have become too big, bloated, and unwieldy. He sees it as an articulation of a cold financial fact: “that the Mafia franchise can’t support the expense of a modern triple-A blockbuster.”

Will Mafia: The Old Country usher in a new era of punchier, shorter, single-player titles from the major publishers? Taking a more cynical perspective, I suspect, should the game fail to live up to financial expectations, Take-Two will use it to firmly condemn this type of game, a test subject in the current economic climate, to the Sicilian catacombs (the company has form here, selling its indie publishing label, Private Division in a bid to focus resources on “core and mobile businesses for the long-term”). Of course, that leaves it to independent and double-A studios to pick up the slack, except their situation is currently grim: there’s little funding available and the days of cheap money (i.e. low-interest-rate loans) are but a distant, halcyon memory.

Or maybe Take-Two will continue to fund these leaner, triple-A-styled titles as a means of – and it pains me to write this – IP management. The Mafia franchise has fans, quite a lot of them in fact, and the fans must be thrown a bone every now and again. For the CEO (the relatively affable Strauss Zelnick in this case) looking to maximise the earning potential of their company’s assets, IP management makes sense; it also happens to be some of the most cynical C-suite board room-speak. Regardless, it’s the kind of logic game makers, and other creatives, are used to toiling under. These developers are carrying on their own noble tradition: wringing art – a work of meaning and insight – from the profit-driven demands and constraints of commerce.